19th Century Sherry

I am a big fan of Sherry. It reminds me of growing up in southern Spain where the old men would be in permanent position at the rickety tables in front of the local bar slowly working their way through the afternoon heat with endless sherry and animated chat. But they are also a strong reflection of the scents and flavours of Andalucia: the salty sea air is always present in Fino, whilst the almond groves and warm spring and autumn sun can be found in Oloroso. And the baking August heat can certainly be found in the rich, raisin flavours of Pedro Ximénez.

I am a big fan of Sherry. It reminds me of growing up in southern Spain where the old men would be in permanent position at the rickety tables in front of the local bar slowly working their way through the afternoon heat with endless sherry and animated chat. But they are also a strong reflection of the scents and flavours of Andalucia: the salty sea air is always present in Fino, whilst the almond groves and warm spring and autumn sun can be found in Oloroso. And the baking August heat can certainly be found in the rich, raisin flavours of Pedro Ximénez.

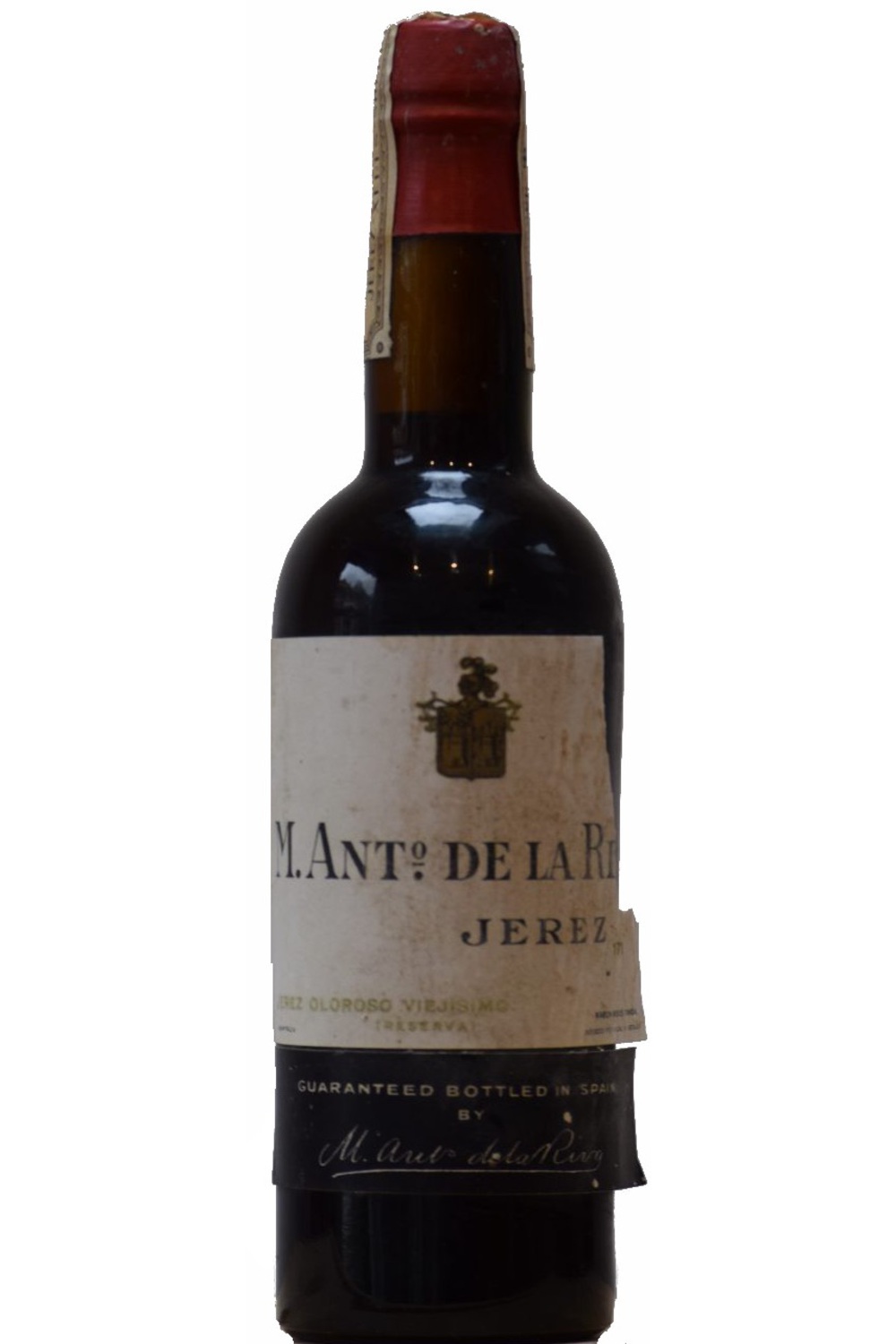

But our purchase of some 1940’s bottlings of dry Oloroso left us not knowing what to expect especially given its history. Made from grapes grown in the 1890’s, aged in barrel during Spain’s brutal civil war, and bottled in the 1940’s when Spain was settling into a dictatorship and the rest of the world was at war, who knew whether any of those Andalucian flavours would be there. Luckily, what’s in the bottle reveals none of the horrors that were happening around it just the delights of nature working its magic. A dark amber, verging on brown liquid with a nose that was surprisingly fresh for its age with plenty of nutty complexity on the palate. Slightly tight and a little coarse on the finish to begin with but nothing a little air couldn’t fix. It mellowed and softened to reveal elegance and finesse without losing the overall dry, fresh finish from a good Oloroso. It tasted not of Andalucía’s history at the time of making but rather Andalucía’s natural environment. To have retained all that complexity of flavour and freshness over the decades is fairly astonishing but very telling of what a well-produced sherry can do.

Antonio de la Riva was set up in the mid 1800’s by Manuel Antonio de la Riva y Pomar when he moved to Jerez and purchased an old but established bodega. Included in the purchase were some rather old but very fine soleras which, combined with well-established and well located vines, earned him prestige within the industry and a reputation for high quality sherry. His sons took over production when he died in 1909 and continued to grow the firm’s reputation. Nothing much changed until the early 1970’s when the Domecq group bought the bodega. The family remained in control of production for a time but, with the gradual erosion of the sherry industry, the varying parts of the business began to be absorbed into the general Domecq brand and the famous wines started to disappear.

The de la Riva name was nearly lost forever when, in 2017, two winemakers decided to resurrect it by buying the rights to the brand. Willy Pérez and Ramiro Ibáñez have begun making wines from grapes grown in the same locations as de la Rivas original sherries. They have also been gathering soleras and their contents from varying defunct bodegas and gradually bottling them for sale.

We have yet to try the new incarnations of Antonio de la Riva but would highly recommend the originals. They were produced at a time when the sherry industry was booming and the quality coming out of the region was exceptional. The fact that the sherry industry almost collapsed but was successfully revived in the 21st century make these samplings even more poignant.

1940s Antonio de la Riva Viejisimo Oloroso £125 per bottle

1940s Antonio de la Riva Viejisimo Cortado £150 per bottle